Michael Bangerter

Michael Bangerter had a long and distinguished career on television, film and stage, from his first appearance in a potentially controversial Sunday-Night Play in 1960 to the high profile series Capital City almost thirty years later. In between, Michael appeared on some of British television's true classics including Armchair Theatre, The Plane Makers, No Hiding Place, Colditz, The Onedin Line, The Naked Civil Servant, When the Boat Comes In and Doctor Who. As if that wasn't enough he also wrote for both stage and radio, was a reviewer, and had published four collections of poetry.

Michael got his first taste of acting at an early age: "I was about eight, in a tiny production put on by the headmistress - she was the only mistress - of a primary school in Wiltshire. I played a doctor - I remember wearing striped trousers (cut down to size) and an enormous top hat - in those days, before the NHS, doctors were thought to be of a certain class and type - although I would have thought a top hat was going it a bit even for then. The play was put on in the local church hall, and on the way home I remember hearing a couple of village housewives chatting over the fence - "Who were that boy who done the 'doctor' part. He were good weren't he." My first positive crit!"

In spite of this praise, acting wasn't Michael's first choice for a career. But his next role changed all that: "A few years later my parents split up and my father and I moved to Brighton (the town in which I was born). I found myself at a small independent school - a sort of 'Dotheboys Hall'- without the kicking and thrashing. Our English master seemed a shade more enlightened than the rest. Anyway, he encouraged us to put on a play. I played a sixty-year-old Scrooge-like character. During the rehearsals he said to the rest of the class, "Here is boy of fourteen who plays this sixty year old man better than I could - and I'm forty five." Well, what more did I need? My first ambition of becoming a barrister - I'd recently seen Robert Donat in the Winslow Boy - was instantly eclipsed."

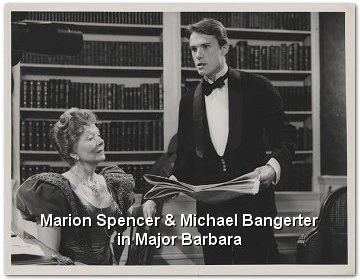

Michael persuaded his father to let him take lessons at a drama school in Brighton. "One of my contemporaries there was Geraldine Newman, and I believe Derek Francis and Donald Sinden were associated with the place at some time or other. It wasn't long before I was entering competitions at the Brighton Festival. I didn't think much of it at the time, but I think I was one of the school's more successful pupils - I used to win most things. In my final competition I played Clemence Dane's Richard II. The rules stated that you could play either Clemence Danes's 'Richard' or Shakespeare's 'Richard'. I shared first prize with Peter McEnery, who played Shakespeare's. Years later, when I was rehearsing Major Barbara for Granada TV, the director, Stuart Burge, took me along to meet Christopher Fry whose play, Curtmantle, was about to begin rehearsals ' he had recommended me for a part. Unfortunately it had just been given to Peter McEnery. A pity we couldn't both have played it - on alternate nights!"

During that period Michael appeared in The Shrike at the Theatre Royal, Brighton: "I played a lunatic in an asylum - although all I did was stand around. The leads were played by Constance Cummings and Sam Wanamaker - my first 'paid job' - I think I got a fiver and very grateful I was too. Later, in the school holidays, I managed to join a repertory company in Horsham at £1.00 a week. A local bank manager doubled as the Horsham theatre critic and gave me a positive review for playing another sixty year old - "Surprisingly good is young Michael Laurence" (my temporary alias - no doubt influenced by Olivier) "pathos is never allowed to become bathos in a firmly controlled performance." I felt this was a genuine review as I wasn't much good to his bank financially. Soon after this I was called up to do National Service. I joined the R.A.F. and was soon posted to Germany - I didn't get back to Sussex for almost two years. I was lucky in my posting, as the headquarters I landed up at had a thriving dramatic society and I was cast in a number of plays. The highlight was when we won the inter services award for the best dramatic production - I still have the rather fine little bronze and chrome trophy. I don't know whether it was design or again luck, but my roommates - we were given not huts, but quite comfortable rooms - were both aspiring actors. Alan Howard became a leading man at Stratford and Philip Elsmore a well-known ITV newsreader."

After being discharged from the RAF it was clear that Michael only wanted to pursue one career: "One of the first things I did when I got back to England was to apply for a place at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art. I was lucky to be accepted on my first application and to receive a scholarship and later a small bursary. Whilst waiting for the course to begin I found much needed work at the Brighton Metropole as a fourth floor valet - got the sack after a month or two for dropping an armchair down two flights of stairs. I did, however, manage to save some money from that job, helped by a generous tip from the then Earl of Bute who asked me to "unpack him". This I did quite inexpertly, not being quite sure where any of his stuff should go. I also learned how to iron a woman's evening dress - a skill not much required in later years."

In 1960, following a production of Tea and Sympathy at the Theatre Royal, Windsor, Michael landed his first role on television in BBC's Twentieth Century Theatre series. The 'BBC audition' was one that almost every young actor leaving drama school would have gone to. "They used to take place in Lower Regent Street. They were set up to help BBC directors and producers cast a role when they had exhausted all other means. As far as I can remember, no actor ever thought he/she would get anything from it except the experience of doing an audition. I think I did a piece from The Seagull (Konstantin). This was only a few weeks before I got the part. Anyway, I was rung up at about ten one evening by Stephen Harrison - he'd tried to get me earlier - asking me if I would read for the role of Ainger the following morning. I read it and they offered it to me immediately.

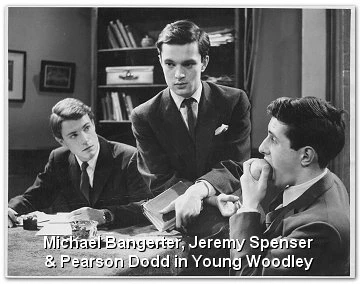

The play in question was Young Woodley, about a shy and sensitive 18-year old schoolboy who has an affair with the housemaster's young wife. It was controversial enough to be banned when it was originally presented for the British stage in 1925. One can only imagine that it may also have caused a stir in 1960-the more openly enlightened 'swinging Sixties' era still a few years away. I wondered if any of the cast were aware of how it might be received by British television viewers? "Well, put it this way, there was still a shock-able element in the British public - bearing in mind that we still had a 'fifties' mentality. But, of course, the shock element was nothing much compared with what it would have been in the 'twenties'. No, I don't think any of the cast was especially aware that we were performing something risque - anyway actors are not easily shocked! About that time I played opposite Brenda Bruce in an ITV production (Probation Officer) - as far as I can remember that also was centred on the involvement of a very young man and a much older woman. Of course, the 'public school' setting of Woodley would have given it more acute salaciousness."

I wondered how this first taste of television appealed to Michael and how it compared to playing live theatre: "I found television acting enjoyable. The greater intimacy, eye contact, etc., allowed a subtlety not easy to achieve in the theatre. I took to it well. Having said that, the stress of attempting to get everything right first time was nerve-racking. In those days there was no rehearse/record facility. The old ampexing machines were in short supply and were whipped away the moment the performance was over - no second chances. It was almost as bad as doing it live - which I once did, playing the lead in an episode of The Planemakers, in front of six million viewers - that was hairy!"

Michael received very favourable reviews for his role in Young Woodley and it helped his career considerably. "It was reviewed by The Critics on the Third Programme, and I remember being very surprised when Ivor Brown (who had written a definitive book on Shakespeare in the 'forties') picked my performance out as one of the best, although he didn't mention me by name, only as "the young man who played Ainger". Stephen Harrison rang me the following morning to congratulate me and to say that if I'd had an 'easier' name, Brown might have mentioned it! Alistair Sim - a friend of Jeremy Spenser's - liked my performance very much, and Margaret Johnston recommended me to her husband, Al Parker (probably the best agent in London at that time). Within a week or so I'd signed a seven year contract with him.

Another consequence of this production was that Michael started to receive fan mail. However, it didn't go to his head: "All I did was to reply to the letters. Most were from young girls, but a few were intelligent letters from older viewers. There were no screaming fans outside my flat. Although one girl did get my phone number from the BBC - she pretended she was my sister and hadn't seen me for years. She rang me and said that she was at a tube station near where I lived and would I meet her - of course I didn't! I don't think the BBC would be giving out that sort of info now!!!"

More TV plays followed including an Armchair Theatre production - A Degree of Murder, an ITV Television Playhouse - Johnny Dark, Royal Foundation a play written by Simon Raven and directed by Stephen Harrison (Young Woodley director) and Mother's Sense of Fun for Associated Rediffusion, which was an Angus Wilson short story adaptation, and several ITV Play of the Week's including For King and Country, Tunnel Trench and George Bernard Shaw's Major Barbara. Michael's role in Tunnel Trench was especially singled out for praise by the Daily Telegraph critic: "The sincerity of the play has clearly infected the Granada people. It was handsomely mounted and tautly directed; the honesty of Robert Morris's and Michael Bangerter's playing carried off the dated sentimentality of the relationship between the central characters."

The period following this production found Michael gainfully employed on both television and the theatre "I did quite a lot of theatre work in the middle and late sixties, and on into the seventies: 1965, the Pitlochry Festival: 1966, Much Ado about Nothing at the Ludlow Festival: 1967, Theatre Royal Windsor: 1968, The Belgrade Theatre, Coventry. However, I got quite a lot of work in television after Pitlochry (1965) because the leading director there for the season was Jordan Lawrence an eminent BBC producer - he cast me in a number of productions subsequent to Pitlochry." There were also appearances in the ITC series Gideon's Way and The Liars for Granada, plus some documentaries.

The 1970s proved just as productive with several productions standing out for Michael, namely The Naked Civil Servant, A Bridge Too Far, and O Lucky Man. Then at the end of that decade there was the National Theatre production of Early Days (later transferred to the Comedy Theatre), directed again by Lindsay Anderson and written by David Storey. "We took Early Days to Canada and America, and did a British tour and a TV production of it." But one other role never came off: "I was contracted to appear in Britannia Hospital for Lindsay, but because of a technician's strike the film was delayed and I was unable, due to other commitments, to do it."

In 1984, Michael landed a part in the cult British science fiction show Doctor Who. The story in question, Planet of Fire, received a lot of publicity at the time because it was the first Doctor Who to be filmed on location abroad. The location in this case was Lanzarote, which proved to be quite fortuitous for Michael: "We were living there at the time - restoring an ancient house. We were there on and off for almost five years. It was a lovely place then. We lived in the old capital - a large village really, with five churches. We were the only foreigners in the place apart from a half Spanish half Swiss genius - he had been a scientist and an inventor - he spoke seven languages including Latin and Greek! My wife and two children were extras on the production - an added bonus."

Other roles followed throughout the 1980s; Capital City, Floodtide and Ray Brook's comedy drama Big Deal: "I have a feeling that Big Deal was the final TV appearance." Although still very much in demand, Michael made what was at that time an awkward decision. "When I returned from the Canary Islands things seemed to have changed - casting directors were not easily rung up, productions were being cancelled - actors were doing other jobs apart from acting (semi-permanent jobs). This doubling up seemed the 'norm'. During that period I did act in a new play by Vaclav Havel, Largo Deselato, directed by Claude Whatham and adapted for British theatre by Tom Stoppard (he also helped direct it). It opened at the Bristol Old Vic - we then took it to Holland and to the Hong Kong Festival. The Holland tour was to celebrate Vaclav being awarded the Erasmus Prize - he was under house arrest in Czechoslovakia at the time. I was due, later, to appear in a prestigious BBC TV production of a new 'Battle of Britain' play, but much to my disappointment, it was axed by Mr Burt! A documentary I was about to do was also cancelled."

Somewhat disenchanted, Michael looked towards another love he'd always had: "I had always been fascinated by poetry and had started to write it. So, I decided to move into Academia - I studied for a number of things, including teaching, and ended up gaining an MA from Lancaster University. I then taught at degree level, gaining Registered Teacher status from Glamorgan University. Also at this time I started to review for magazines and the internet and began to take music composition for the piano seriously - although I am still very much an amateur at it. I did though, compose the music for a radio play in the mid Seventies, and a very bad pop song of mine was produced by United Artists as a 'B' side. Since then I've composed small pieces of music to accompany poetry on two CDs (one of my own poetry and another of Thomas Hardy's)."

Were there any regrets about giving up acting? "I miss the atmosphere, the buzz of the TV and film studios, the fear mixed with excitement when acting in the theatre, and the camaraderie experienced within an amicable cast. Friends of mine could not understand why I moved away from acting. One friend, sadly, now deceased, suggested I had other 'lives', other means of expressing myself. Well, I suppose that was true - and to a certain extent, still is."

"The thing is that unless you are doing something really interesting and good it all seems rather pointless - except for the money, of course - and work then and now - ask any reasonably well known actor - was/is not easy to come by. Olivier's old quote, 'The best part of acting is the drink in the bar afterwards' is sometimes justified."

Although we never met in person, Michael and I both had a thoroughly enjoyable experience communicating via email to write this article and stayed in touch long after it was concluded. So it came as a great shock when I was informed by his family that Michael had passed away on Thursday 25th August 2016, aged 80 years of age. In 2014 Michael was diagnosed with cancer and so began a two year battle and numerous operations. Sadly, he lost that battle on 25th August and passed away peacefully with his family at his side. The one thing that helped Michael, aside from his loving family, was that he maintained his sense of humour to the end.

Published on February 20th, 2019. Written by Laurence Marcus interviewed Michael Bangerter in 2011 for Television Heaven.